What are rare-earth elements and why is everyone looking for them? | Explained

Even when they’re not very scarce in the earth’s crust, they tend to be spread out in low concentrations and mixed together with each other in the same minerals, so they’re difficult and expensive to separate. However, countries worldwide are interested in acquiring them because they’re crucial for high-performance magnets, specialised lighting and optics, catalysts, and other components that underpin many green technologies and electronics.

History and technology

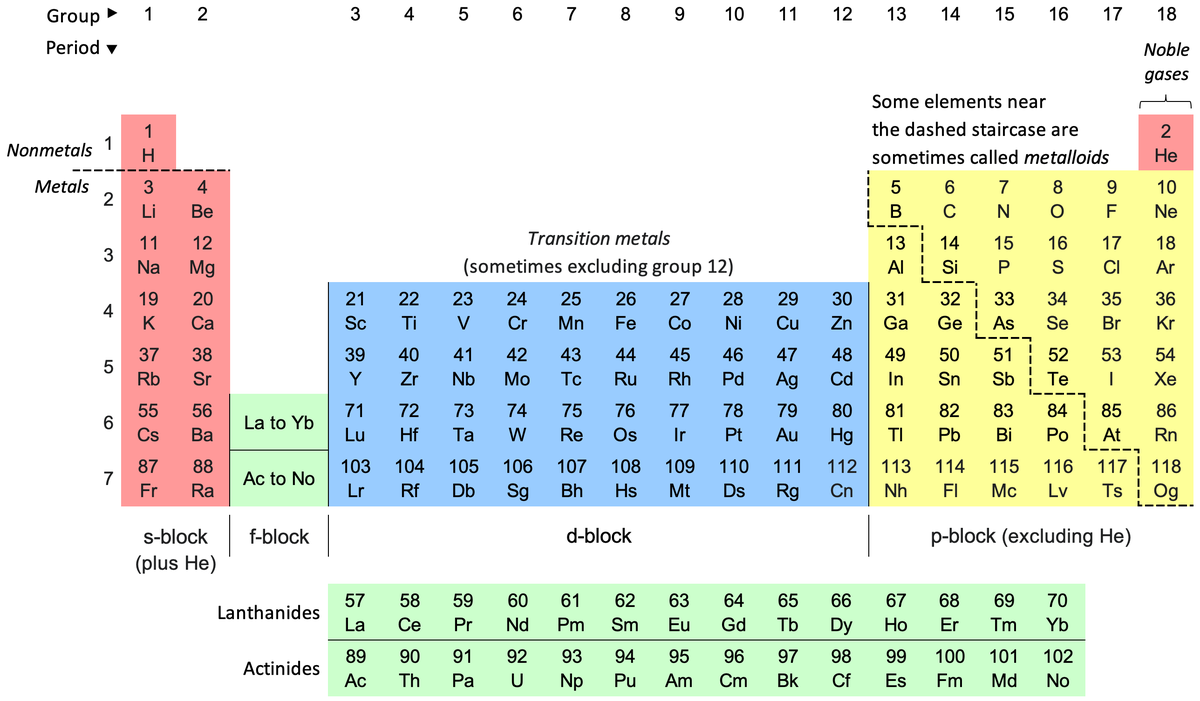

The rare-earth elements are scandium, yttrium, lanthanum, cerium, praseodymium, neodymium, prometheum, samarium, europium, gadolinium, terbium, dysprosium, holmium, erbium, thulium, ytterbium, and lutetium.

They’re called ‘rare earths’ for historical reasons. “Earth” was an old chemistry term for oxide powders and many of these elements were first identified as oxides from which they couldn’t be isolated easily. These elements are also rarely found as pure native metals in nature.

However, people often use the term ‘rare-earth’ loosely, leading to confusion. Some use ‘rare-earths’ to mean only the lanthanides. Some others bundle rare-earths with ‘strategic’ or ‘critical’ elements such as lithium, cobalt, gallium, and germanium even though the latter aren’t rare-earth elements.

The periodic table of elements.

| Photo Credit:

Sandbh (CC BY-SA)

Rare-earth elements show up in many contemporary technologies because of their useful electrical, magnetic and/or optical behaviour. One particularly important application is as permanent magnets.

Neodymium-iron-boron magnets, which are the world’s most common magnet type involving a rare-earth element, and which sometimes also include praseodymium and small quantities of heavier rare-earth elements, are used in motors and generators, including in many electric vehicles and in wind turbines.

Phosphors — substances that emit light when irradiated — also incorporate europium and terbium while dopants in lasers and optical devices (including in fibre optics) use neodymium and erbium. Rare-earth elements are also used in catalysts, glass and ceramics, polishing powders, and other specialised materials.

Magnetic chemistry

In permanent magnets, rare-earth atoms have electrons in the 4f shell that behave differently from the other electrons. The 4f electrons are relatively more localised, meaning they stay close to the nucleus, whereas the other electrons become ‘smeared out’ when they become part of bonds in a solid. As a result the 4f electrons maintain a strong magnetic moment, i.e. they behave very faithfully like small magnets. An atom with multiple electrons like this also behaves more strongly like a magnet.

Every good permanent magnet needs to have two things: a large magnetisation, meaning many atomic magnetic moments can line up in the same direction to make a strong overall field; and stability, which means once the magnetic moments line up, they don’t easily get knocked out of alignment by heat, vibrations or even an opposing magnetic field.

Rare-earth atoms have both. Their 4f electrons can carry relatively large magnetic moments, so they can contribute to strong magnetisation. And because these electrons are localised as well as closely align with the crystal’s preferred direction (due to a property called magnetocrystalline anisotropy) they can ‘pin’ the magnetisation down. Motors and generators that use such magnets work efficiently even at high speeds and high temperatures.

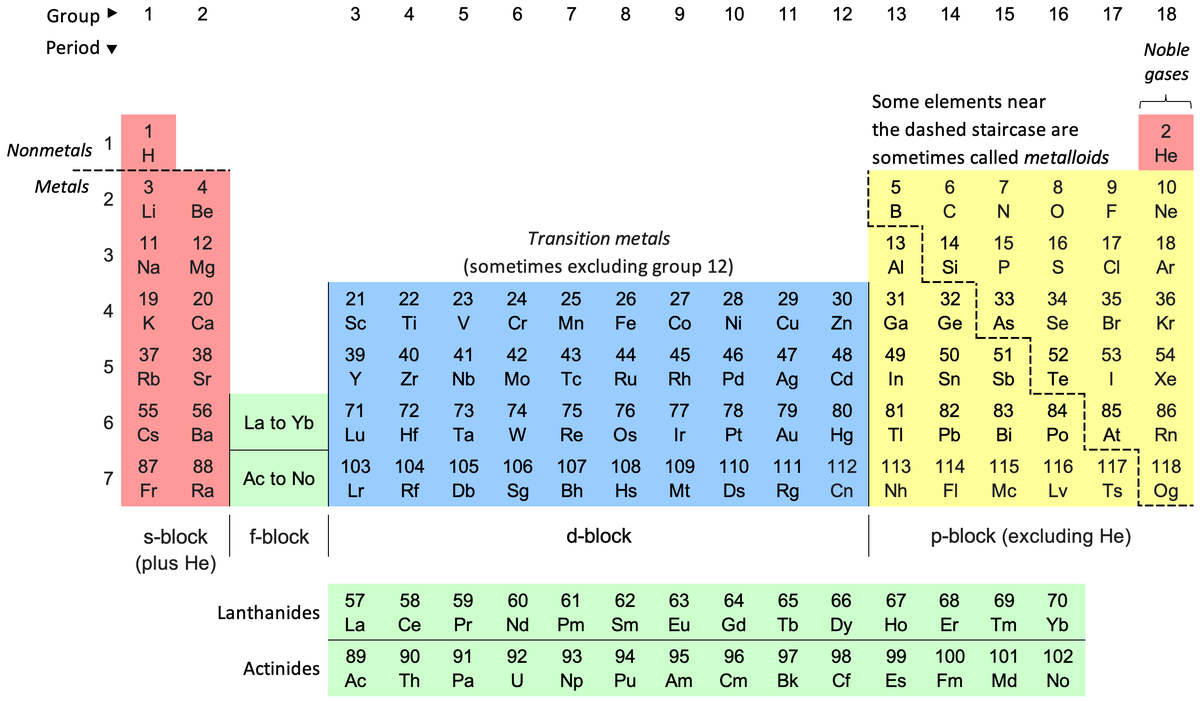

Japanese scientist Masato Sagawa, who invented the neodymium-iron-boron magnet, demonstrates how just 1 gram of the magnet can hold 1.9 kg of water.

| Photo Credit:

Christina.h.chen (CC BY-SA)

Rare-elements are also good phosphors because they produce sharp, stable colours. The idea is to supply energy to such a phosphor at a frequency its 4f electrons are likely to absorb. When they do, the electrons get excited, then de-excited, reemitting the excess energy at a different (but fixed) frequency. We see this emission as light.

Because the 4f electrons sit relatively close to the nucleus, they’re partly shielded from the surrounding solid by the outer electrons. So the exact energy levels of the 4f electrons aren’t much affected by the crystal they’re inside. The light the 4f electrons emit is also concentrated in a small slice of the visible spectrum instead of being a mix of colours.

Rare-earths v. oil

Rare-earth ore deposits that can be mined in an economically feasible way are usually found in a few pockets of rock and soil rather than being spread evenly. Companies start by looking for minerals that carry rare-earth elements in higher concentrations, such as bastnäsite and monazite, or for certain clay deposits in which rare-earth ions are loosely held on the surface of clay particles.

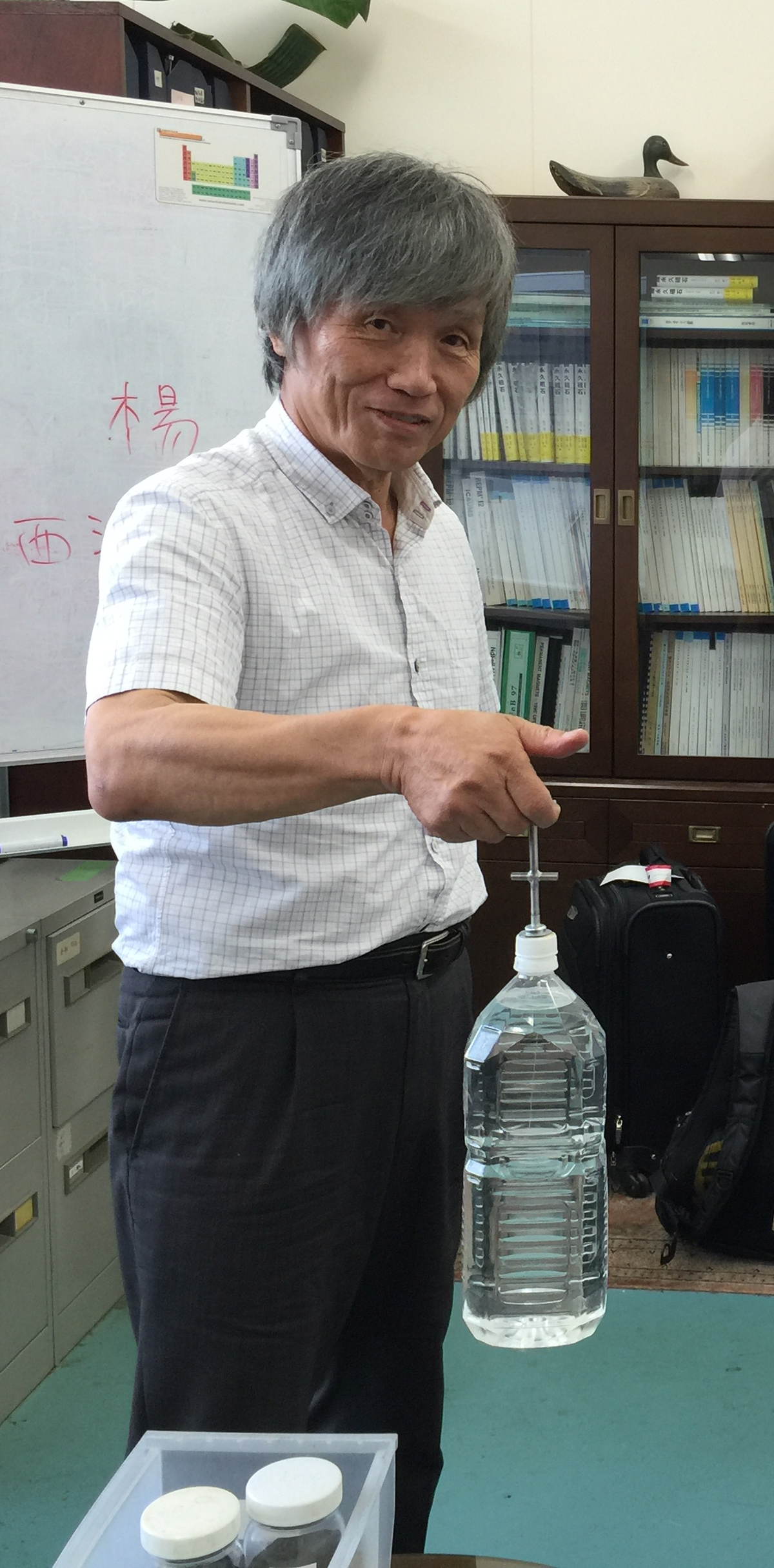

Many mines are open-pit since these minerals are usually dispersed through large volumes of rock and the ore has to be dug out, crushed, and moved in bulk. This is also where some of the environmental complications of rare-earth element value chains first appear: some minerals occur alongside thorium or uranium, so the waste rock needs to be handled carefully. Mines may also need copious amounts of water and specific chemicals to produce an initial concentrate.

A false-colour satellite image of the Bayan Obo open-pit mine for rare-earth elements in the Nei Mongol Autonomous Region, China, in 2006.

| Photo Credit:

NASA

This said, while both rare-earth elements and crude oil have to be extracted and processed before use, the processing step is significantly different — so much so that for rare-earth elements it has emerged as a strategic element.

A refinery uses physical separation plus some chemical reactions to refine crude. Fractional distillation, the main step, works because hydrocarbons’ boiling points are spread out, so just heating and condensing the crude can separate its constituents efficiently at industrial scale.

On the other hand, rare-earth producers start with solids that contain many elements together, and they must be separated at very high purity for applications. The problem is that neighbouring rare-earth ions behave similarly in solution, so the corresponding separation process is voluminous and energy-intensive.

Second, a magnet maker doesn’t want any or all rare-elements but a specific oxide or metal, of a minimum purity. If a separator is short on one element or can’t deliver the required purity, the factory can’t switch one element for another. In the oil industry, however, refineries can swap feedstocks and trade intermediates at scale.

Midstream menace

After mining, the first goal is to make a smaller, richer product. This begins with beneficiation: physically processing the ore to separate more valuable mineral grains from the less. Workers crush and grind the ore to free the grains, then use flotation, magnets or gravity to separately collect different concentrates. The resulting concentrate will still contain many rare-earth elements together, plus other unwanted elements.

Next is chemical cracking, where the producer breaks the rare-earth minerals apart using strong acids or bases or high temperature, converting them into a form that dissolves more easily.

Third is leaching. The cracked material is mixed with a liquid, often an acidic solution, so the rare-earth atoms move into the liquid as ions. Then the producer separates the liquid from the remaining solids; this liquid contains a mixture of all rare-earth ions dissolved together plus some impurities.

The hardest step is separating this mixture into individual rare-earth elements of high purity because these elements often have the same common charge (usually +3) and their ions are similar in size. In a simple chemical reaction, then, the ions behave in roughly the same way.

Industry thus uses a technique called solvent extraction instead. The leach solution is repeatedly brought in contact with an organic solvent that doesn’t mix with water. The solvent contains molecules that prefer to bind with certain rare-earth ions slightly more than others. When the two liquids touch and separate, a little more of one rare-earth element moves into the solvent than its neighbours do. The difference is small, so producers run the liquids through many stages in a row, until the process separates the elements one by one and each element has been collected in a separate stream at high purity.

Producers finally recover the elements from the liquid as a solid by precipitation: they add a compound that bonds with the rare-earth ions and becomes insoluble, falling out of the solution as a solid. The solids are filtered and washed, then heated to remove the water and some other substances, to finally yield a rare-earth oxide. The elements are usually stored and transported as these oxides.

Rare-earth oxide powders are typically heavy and gritty. Clockwise from top-centre: praseodymium, cerium, lanthanum, neodymium, samarium, and gadolinium.

| Photo Credit:

Public domain

If a manufacturer needs an element as a metal, the oxide is subjected to a reduction reaction in which the oxygen atoms react away from the oxide.

Some rare-earth ores contain thorium or uranium, which can make some waste streams radioactive and harder to store safely. Acids and bases can also create hazardous wastes if they aren’t captured, treated, and recycled properly.

China’s dominance

Because rare-earth elements’ midstream refinement is so arduous, a country can have substantial deposits in the ground but still have to depend on other countries if it doesn’t have the means to convert the ore into rare-earth oxides.

According to the US Geological Survey’s Mineral Commodity Summaries, the world has more than 90 million tonnes of rare-earth-oxide equivalent. Some notable national reserves include China (44 million tonnes, MT), Brazil (21 MT), India (6.9 MT), Australia (5.7 MT), Russia (3.8 MT), Vietnam (3.5 MT), the US (1.9 MT), and Greenland (1.5 MT). Note: these estimates exclude scandium.

On December 23, Japan announced that in January and February 2026, it would excavate mud rich in rare-earth elements from 6 km underwater off Minamitori Island.

The International Energy Agency has estimated that China’s position is especially strong in separation and refining, accounting for around 91% of global production, and around 94% of the production of sintered rare-earth permanent magnets.

Since many fast-growing green technologies require motors, generators, and other hardware where high-performance magnets are crucial, countries are focusing on building refining and magnet-making capacity, rather than just approving new mines.

Discover more from stock updates now

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.