The “biggest blunder” of Einstein’s life

The greatest achievement of a scientist who can lay claim to being the most famous and influential scientists of all time is his theory of relativity (yes, the iconic equation E = mc2 stems from this). What we now see as the theory of relativity is two interconnected theories — special relativity, which Einstein came up with in 1905, and general relativity, which he came up with in 1915. We wouldn’t be getting into specifics here, but by showing that space and time are relative and not absolute, that they form a fabric called spacetime, that gravity is the curvature of spacetime caused by mass and energy, and that the speed of light is constant for all observers, Einstein revolutionised physics as we knew till then.

Einstein’s constant

If you were under the impression that scientists rest on their laurels, especially after producing theories as groundbreaking as this one, you couldn’t be further from the truth. Given that his theories had far-reaching implications, there were some inconsistencies, and Einstein meant to smoothen them.

When investigating what his general relativity had to say about the universe as a whole, Einstein bumped into a problem. The field equations of relativity curiously resulted in a null solution when assuming a static, uniform distribution of matter in the universe, the prevailing theory of the time.

To counter this, Einstein modified his field equations in 1917 by adding a new term λ (denoted by lambda), where λ was a cosmological constant. This addition forced the equations to predict a static universe, in tune with the thinking of the time.

Hubble hints at expansion

Our view of the universe, however, was about to be turned upside-down just over a decade after the cosmological constant came into existence. The man responsible for that was American astronomer Edwin Hubble, a name you’ll surely recognise owing to the famous space telescope that now bears his him.

Having turned to the study of stars only after his father’s death in 1913, he was hired at the Mount Wilson Observatory after his return to the U.S. following his stint with the U.S. Army during World War I. With access to the most cutting-edge equipment of the times thanks to the observatory, Hubble discovered a number of new galaxies from 1919 onwards.

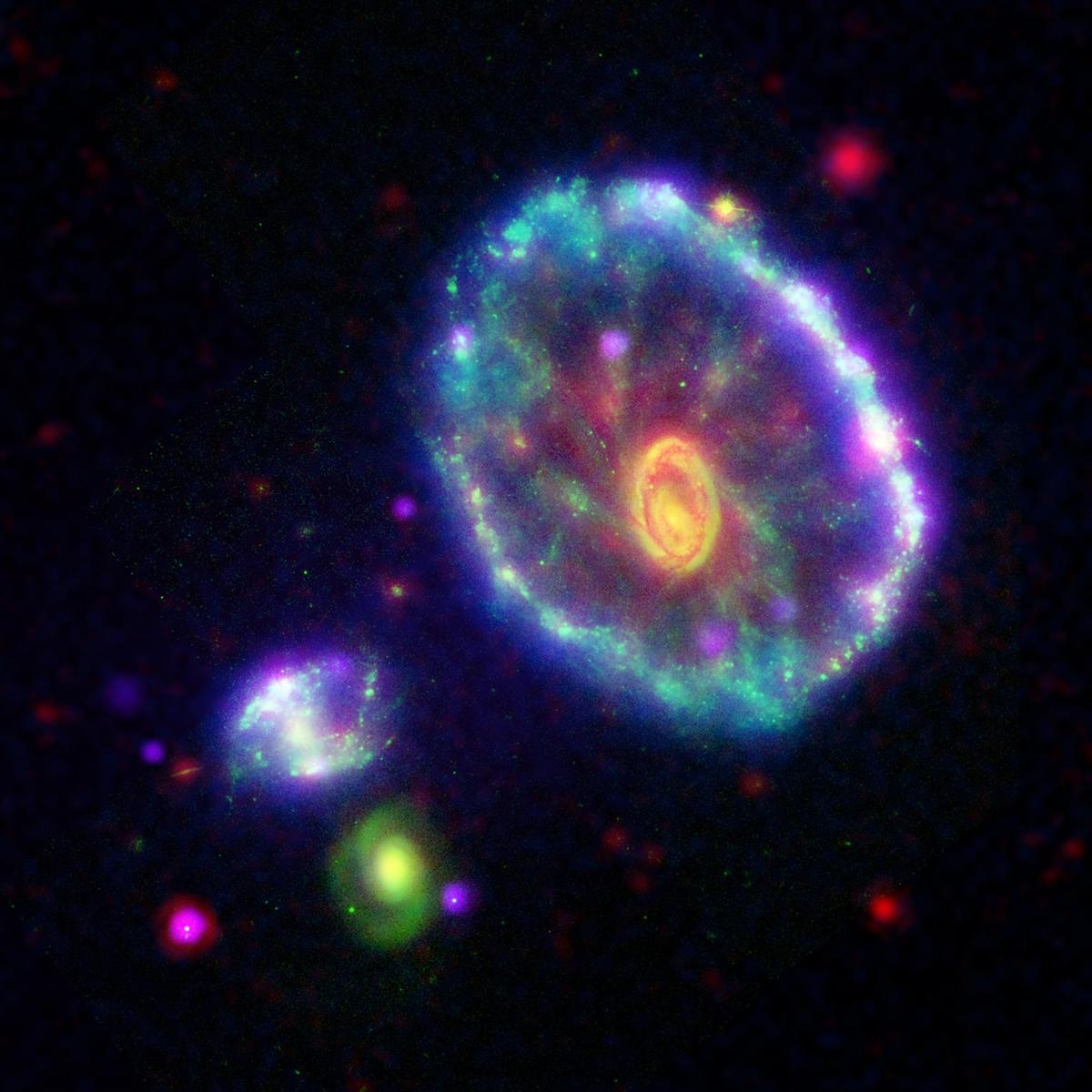

This false-colour composite image in 2009 shows the Cartwheel galaxy. The universe holds many questions for us. The “biggest blunder” is one of them.

| Photo Credit:

AP

Building on the work of other astronomers before him, Hubble was able to measure the rate at which a galaxy was moving towards or away from our Milky Way by observing the changes in wavelengths of light coming from the galaxy — a measurement called the Doppler shift (the principle is the same as what you experience when an ambulance goes past with its sirens blaring; while it is the pitch of the sound that changes as the siren approaches, blares by, and moves away, it is light wavelength in the case of galaxies — bluer when moving towards, and redder when moving away).

It was in 1929 that Hubble and his colleagues published their evidence of a linear relation between the redshifts of spiral nebulae and their radial distance. The paper, simply titled “A Relation between Distance and Radial Velocity among Extra-Galactic Nebulae,” was communicated to the National Academy of Sciences on January 17, 1929 and demonstrated that many visible galaxies seemed to be speeding away from ours.

Despite being central to a discovery as momentous as this — for Hubble and his co-authors had observed and reported the expansion of the universe — Hubble even stopped short of saying it in so many words. While the data presented declared the obvious, Hubble let the readers come to their conclusions, choosing, instead, to say that it was “premature to discuss in detail the obvious consequences of the present results.”

One of the consequences

The interpretation meant that the static universe hypothesis received its final blow. The expanding universe concept proposed in the 1920s by Russian physicist and mathematician Alexander Friedmann and Belgian priest and cosmologist Georges Lemaître quickly gathered steam.

Theorists lost no time in jumping ships as they switched their attention to non-static relativistic models of the universe. Not one to be left behind, Einstein quickly abandoned static cosmology, and along with it, the cosmology constant that he had introduced in the first place.

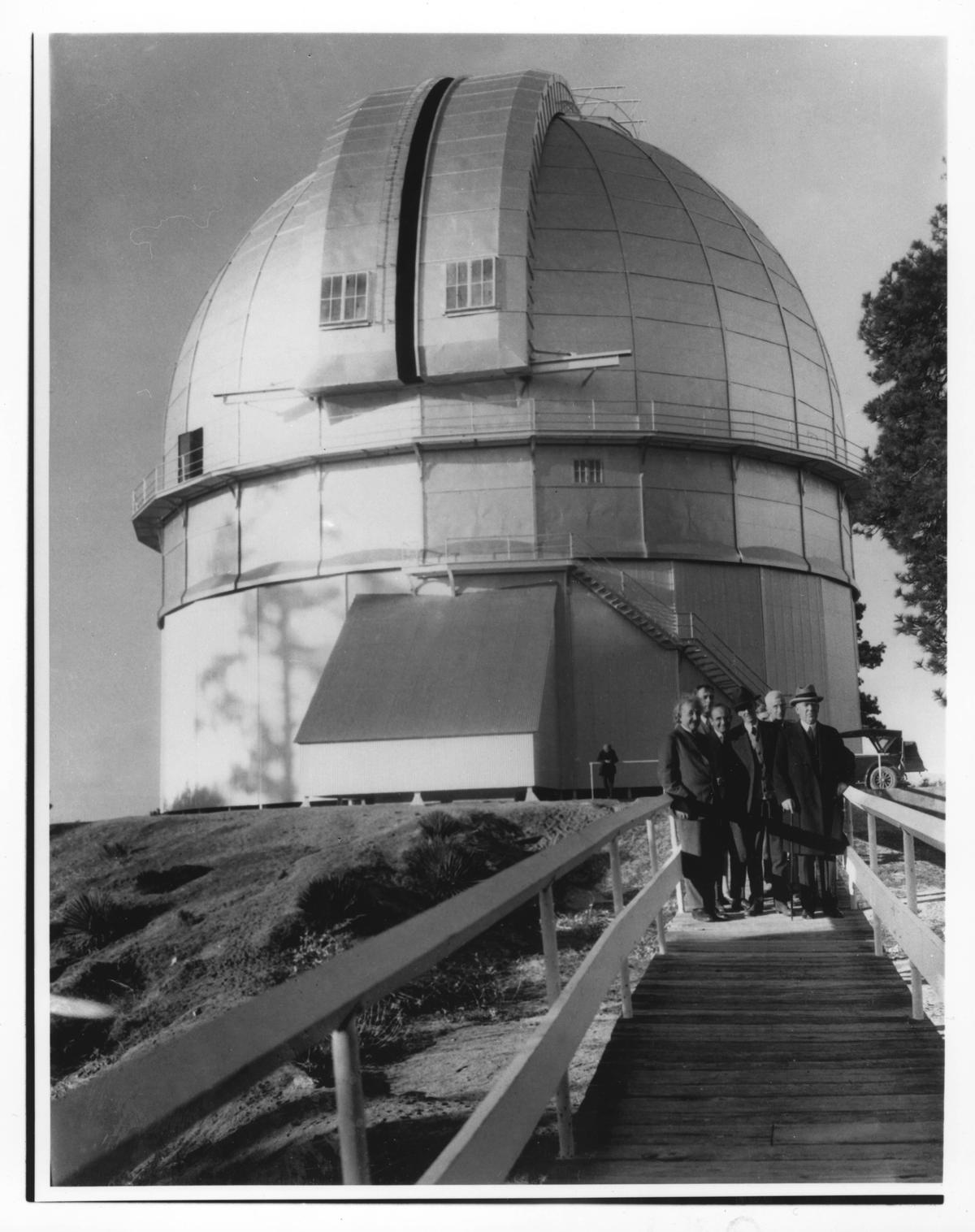

That wasn’t before he had a chance to visit Hubble and other astronomers at the Mount Wilson Observatory in 1930-31. In addition to expressing his support for Hubble’s findings, Einstein also thanked him for the support the observatory’s findings gave to relativity theory.

Albert Einstein (left) and Edwin Hubble (second from left) seen on the footbridge leading to the 100-inch telescope dome, Mount Wilson Observatory.

| Photo Credit:

Image courtesy of the Observatories of the Carnegie Institution for Science Collection at the Huntington Library, San Marino, California.

By 1931, Einstein had a model of the expanding universe not unlike that of Friedmann’s. But while Friedmann and Lemaître employed the cosmological constant in their work, Einstein ditched it completely, once and for all.

Einstein, in fact, went so far as declaring the cosmological constant as both unsatisfactory and redundant. This was because it gave an unstable static solution and the fact that relativity could account for an expanding universe without the term. He never included the cosmological constant thereafter in any of his writings about cosmology until his death in 1955.

It was in the following year that Soviet-American physicist George Gamow wrote an article for Scientific American that included an interesting tidbit. Writing about the Big Bang model, Gamow mentions that “Einstein remarked to me many years ago that the cosmic repulsion idea was the biggest blunder he had made in his entire life.” Gamow included this incident in his 1970 autobiography as well and the story was soon elevated to legendary status.

Was it a mistake?

The verdict on that is still not out. While there’s no doubt that the universe is expanding, astronomers and cosmologists aren’t so sure about chucking out the cosmological constant altogether.

Late in the 1990s, the scientific community came to the consensus that the rate of cosmic expansion is increasing. This, they believed, was driven by a mysterious force called dark energy. And ironically, Einstein’s cosmological constant turned out to be the best fit for dark energy. Recent findings in 2025, meanwhile, challenge the current consensus and state that the universe’s expansion might actually be slowing down.

On top of all this, there’s also the suspicion that Einstein never actually said what Gamow said he did. Yes, Einstein summarily dismissed the cosmological constant from all his writings after a point. But did he actually call it the “biggest blunder” of his life?

There are those who believe Einstein never said it, and that it probably was an invention on the part of Gamow. Known to be a prankster of sorts (find out about the Alpher–Bethe–Gamow paper, or αβγ paper) with a reputation for hyperbole, you couldn’t put it past Gamow.

On the other side are those who believe Einstein said it. This includes an Einstein scholar who confirms that in addition to Gamow, two other scientists — American theoretical physicist John Archibald Wheeler and American cosmologist Ralph Alpher (the same one who authored the paper Gamow pranked with) — have also recollected the incident wherein Einstein calls out his “blunder” in a book and an online message board.

Did Einstein call the cosmological constant the “biggest blunder” of his life? Is the cosmological constant a mistake, or does it actually carry meaning? Time probably has the answers to these.

Discover more from stock updates now

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.