Rupee’s spectacular fall: Why RBI isn’t targeting a price band, but inflation — the ‘Impossible Trilemma’ explained

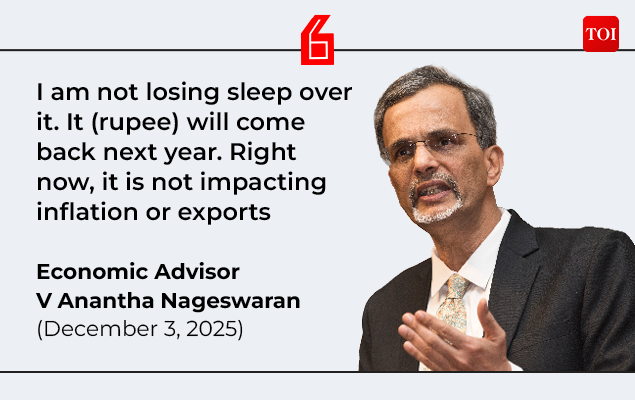

In early December 2025, the Indian rupee reached a key milestone when it surpassed Rs 90 per dollar for the first time. The rupee had been falling steadily throughout the year, as foreign investors sold off Indian stocks and US tariffs made Indian exports less competitive.However, on December 5, 2025, Reserve Bank of India Governor Sanjay Malhotra delivered a clear message”We don’t target any price levels (of rupee) or any bands. We allow the markets to determine the prices.”On the rupee’s slide, Chief Economic Adviser V. Anantha Nageswaran told reporters that the government wasn’t “losing sleep” over the currency’s decline. The falling rupee, he insisted, was “not affecting inflation or exports” and should “improve next year (2026).”

These weren’t throwaway lines. They reflected a fundamental economic framework – the impossible trilemma – that constrains every modern central bank and explains why India prioritizes inflation control over defending arbitrary currency levels. The rupee’s approximately 6% depreciation in 2025 wasn’t a policy failure. It was the deliberate price of maintaining monetary independence.

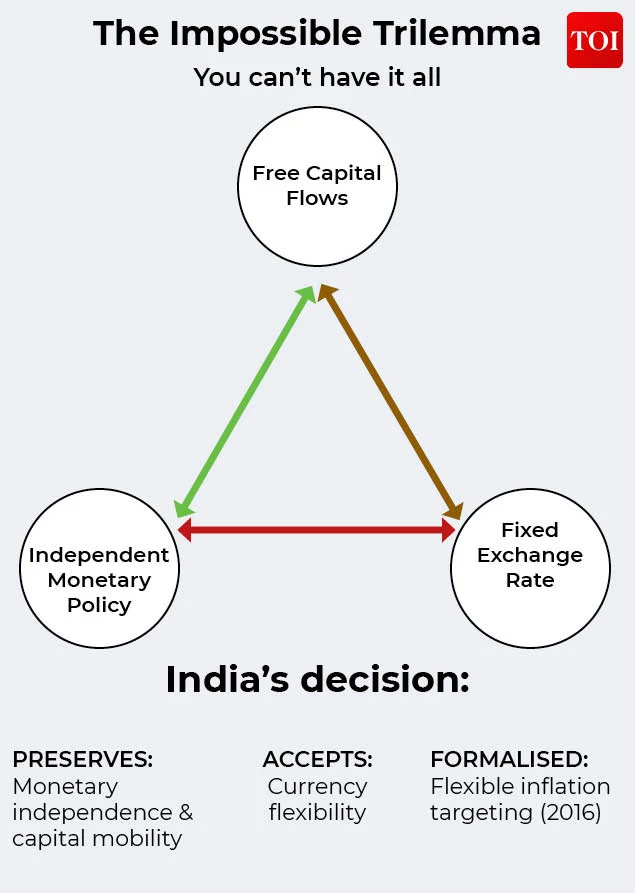

The Impossible Trilemma: India’s two-out-of-three choice

The impossible trilemma, explained by economists Robert Mundell and Marcus Fleming in the early 1960s, presents one of the most fundamental constraints in international economics.It states that it is impossible to have all three of the following at the same time:

- Free capital flows – allowing money to move across borders without restrictions

- Independent monetary policy – setting interest rates based on domestic needs

- Fixed exchange rate – keeping the currency stable against foreign currencies

As Paul Krugman famously summarized: “The point is that you can’t have it all: A country must pick two out of three.”

Understanding each corner of the trilemma

Free Capital Flows: This means allowing capital—both foreign and domestic—to move in and out of a country without restrictions. Investors can buy Indian bonds or stocks, and Indians can invest abroad without facing capital controls. The benefit is access to global capital markets, which can fund growth and development. The risk is volatility—hot money can rush in during good times and flee during crises.Independent Monetary Policy: This is the central bank’s ability to set interest rates based purely on domestic economic conditions—inflation, growth, unemployment—without worrying about external pressures. If inflation is rising domestically, the RBI can raise rates. If growth is slowing, it can cut rates. This independence is crucial for managing the domestic economy.Fixed Exchange Rate: This means committing to maintain the currency at a predetermined level against another currency (usually the US dollar) or within a narrow band. The benefit is predictability for trade and investment. The cost is the loss of flexibility to respond to economic shocks.

The mechanism: Why you can’t have all three

If a country wants to maintain a fixed exchange rate while allowing capital to flow freely across its borders, it must sacrifice control over its monetary policy. Here’s why:Suppose India tried to fix the rupee at Rs 80 per dollar while keeping borders open to capital flows. If the RBI increased interest rates to fight domestic inflation, higher returns would attract foreign capital, creating demand for rupees and pushing the exchange rate below Rs 80—say, to Rs 78. To maintain the Rs 80 peg, the RBI would have to sell rupees and buy dollars, increasing money supply and negating the interest rate hike’s anti-inflationary effect.Conversely, if the RBI cut rates to stimulate growth, capital would flee to higher-yielding assets abroad, weakening the rupee beyond Rs 80– say, to Rs 82. To defend the peg, the RBI would have to sell dollars and buy rupees, reducing money supply and negating the rate cut’s growth-boosting effect.In both cases, the attempt to maintain a fixed exchange rate forces the central bank to intervene in ways that undo its monetary policy actions. The interest rate becomes a tool for managing the exchange rate, not the domestic economy.As Ranen Banerjee, Partner and Leader, Economic Advisory Services & Government Sector Leader at PwC India, told TOI “The trilemma refers to making a monetary policy choice between first having fixed or floating interest rates, second free or restricted capital mobility and third having an independent capability to set interest rates. A monetary policy of a country has to make a choice of any two of these and cannot make a choice to have all three.“

India’s choice: Monetary Independence and Capital Mobility

India’s choice has been clear since the 1990s economic liberalization: prioritize monetary policy independence and capital account openness, accepting exchange rate flexibility as the necessary trade-off.“In the case of India, we have made a choice of having independence in setting interest rates and having free capital mobility,” says Ranen Banerjee. “Thus, we will not have the ability to control exchange rates and it has to be floating. If we attempt to control the exchange rate, we will have to make a compromise on either our ability to set interest rates or bring in capital flow controls. Hence in the current policy choices made in the monetary policy, the rupee will find its own level with the Reserve Bank interventions being only for management of volatility as stated in its policy.“In 2016 a flexible inflation-targeting framework was adopted, which made price stability—targeting consumer price inflation at 4% with a tolerance band of ±2 percentage points—the RBI’s primary statutory objective.

India’s currency regime: Managed float in practice

While India officially follows a “market-determined” exchange rate system, in practice it operates what economists call a “managed float” regime. The RBI doesn’t target a specific exchange rate level, but it does intervene to manage excessive volatility.

How RBI interventions work

The RBI’s forex interventions typically occur through:

- Spot market operations: Directly buying or selling dollars in the spot market. When the rupee weakens too sharply, the RBI sells dollars (buying rupees), increasing dollar supply and supporting the rupee. When the rupee strengthens too much, it buys dollars (selling rupees), building reserves.

- Forward market operations: The RBI also operates in the forward market, where it can buy or sell dollars for future delivery. This affects forward premiums—the cost of hedging currency risk—without immediately impacting spot rates.

- Swap operations: The RBI occasionally conducts buy/sell swaps, where it simultaneously buys and sells dollars for different tenures. In December 2025, it announced a $10 billion dollar-rupee buy/sell swap to absorb excess dollar liquidity and cool elevated forward premiums.

The key distinction: These interventions aim to smooth volatility, not defend a specific rate. As Governor Malhotra clarified, “We don’t target any price levels or any bands.”

The reserves buffer

India’s foreign exchange reserves—currently around $686.8 billion (as of January 2, 2025)—provide the ammunition for these interventions. However, using reserves comes with costs. Each dollar sale drains reserves, and aggressive defence can deplete this buffer, leaving the country vulnerable during a genuine crisis.Sachchidanand Shukla, Group Chief Economist at Larsen & Toubro, points to another constraint: “RBI’s large net FX short forward positions act as a drag on the INR. While the RBI can roll over on maturity dates, it risks making it cheaper for speculators to fund long-USD positions and giving delivery would adversely impact durable liquidity, which could impact monetary transmission and weigh on the FX reserves.”

Why Inflation takes priority over exchange rate

India’s inflation-targeting framework, adopted in 2016, mandates the RBI to prioritize price stability. The framework defines this as targeting Consumer Price Index (CPI) inflation at 4% with a tolerance band of 2-6%, according to Inflation targeting framework 2016. In 2025, inflation has remained extraordinarily low, dropping below even the 2% lower tolerance band for three consecutive months (September-November).This success wasn’t accidental. It required consistent focus on domestic price stability, sometimes at the expense of currency stability. Between May 2022 and February 2023, the RBI raised the repo rate by 250 basis points (from 4% to 6.5%) to combat post-pandemic inflation, even as this widened interest rate differentials with other economies and put upward pressure on capital outflows. As Ranen Banerjee notes, maintaining this independence is crucial: “Hence in the current policy choices made in the monetary policy, the rupee will find its own level with the Reserve Bank interventions being only for management of volatility as stated in its policy.”

When the trilemma breaks: Historical lessons

History is evident with crises where nations tried to “have it all” and failed spectacularly:

1992 UK (Black Wednesday)

The UK tried to maintain the pound’s peg to the Deutsche Mark within the European Exchange Rate Mechanism while allowing capital flows. When economic conditions diverged—Germany needed high rates to fight reunification inflation while the UK needed lower rates to combat recession—the peg became unsustainable.Speculators, most famously George Soros, bet against the peg. On September 16, 1992, the Bank of England spent billions defending the pound and raised interest rates from 10% to 15% in a single day – but since it failed the implementation never happened. The UK was forced to exit the mechanism, devalue the pound, and abandon the peg. Soros reportedly made over $1 billion, according to Investopedia.The lesson: No amount of reserves can defend an overvalued peg against determined market forces when fundamentals don’t align.

1997 Asian Financial Crisis

Thailand, Indonesia, and South Korea attempted to maintain currency pegs with open capital markets while their economies overheated. When the Thai baht came under speculative attack in July 1997, Thailand spent its reserves defending the peg before finally floating.The baht collapsed 50% within months. The crisis spread to Indonesia (rupiah fell 80%), Malaysia, and South Korea. The IMF had to arrange bailout packages. Millions lost jobs, incomes, and savings.The lesson: Fixed pegs with open capital accounts become untenable when underlying economic fundamentals—current account deficits, asset bubbles, private sector debt—turn unfavorable.

2001 Argentina

Argentina maintained a 1-to-1 dollar peg for a decade while allowing relatively free capital flows. When the economy slipped into recession in 1998-1999 and capital began fleeing, Argentina should have either floated the peso, imposed capital controls, or implemented painful deflation to restore competitiveness.It did none of these decisively. Reserves drained, confidence collapsed, and in December 2001, Argentina froze bank deposits, defaulted on $95 billion in sovereign debt, and abandoned the peg, according to Cato Institute. The peso eventually fell to 4-per-dollar. GDP contracted 20%, unemployment hit 25%, and poverty soared. . In 2001, the debt-to-GDP ratio was 55 percent, although the figure increased to 150 percent after the depreciation since most of the debt was denominated in foreign currency, according to a Brooking study. The lesson: Trying to maintain all three corners of the trilemma during a crisis only delays and amplifies the eventual collapse.

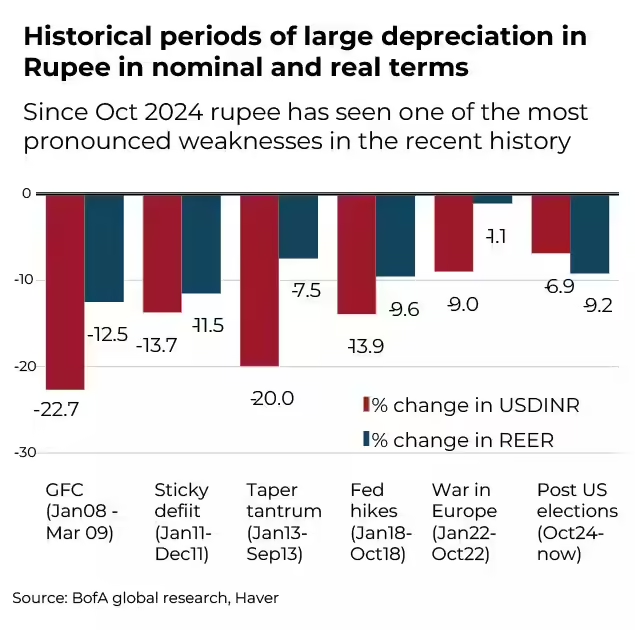

The Rupee in 2025

The rupee’s performance needs context. While it depreciated approximately 6% in 2025—becoming one of Asia’s weaker currencies—this follows a year of relative stability. Why the Rupee weakened in 2025Multiple factors converged to pressure the rupee in 2025:

1. Monetary policy divergence

At the other end of the spectrum, India has already seen rate cuts along with other easing measures, which have significantly narrowed its interest rate differential with regional peers and put downward pressure on the rupee, an analysis by Haver Analytics said “This has significantly reduced India’s interest rate differential with regional peers and placed downward pressure on the Indian rupee.” Meanwhile, the US Federal Reserve kept rates elevated for longer than expected, widening the US-India rate differential.

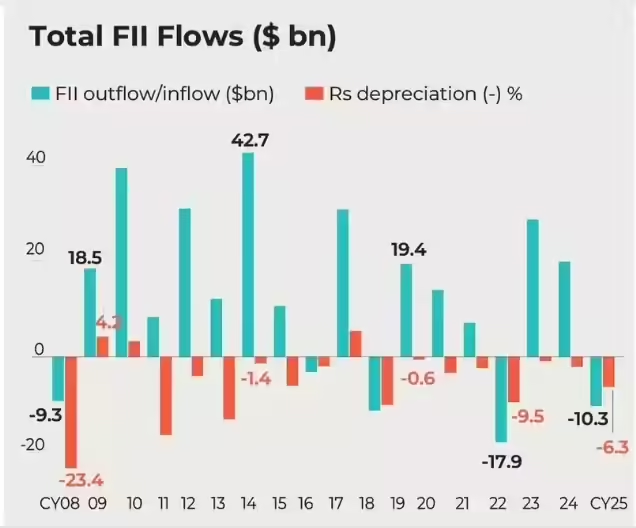

2. Foreign portfolio outflows

Foreign institutional investors turned net sellers of Indian equities and debt in 2025. The outflows were driven by:

- High US treasury yields making dollar assets attractive

- US tariff threats on Indian exports

3. Current account pressures

India’s current account deficit—though still modest at 1.1% of GDP (December 2025)—reflects ongoing import demand, particularly for oil. As Sachchidanand Shukla notes: “The absence of positive newsflow on the India-US trade deal and expectations of a larger BOP [balance of payments] deficit continue to hurt INR.

Source- BofA

4. RBI intervention

“This backdrop forces RBI to prioritize monetary independence and open capital account as inflows, especially FDI are important, and hence it allows INR to be flexible/gyrate,” explains Sachchidanand Shukla. “Also, an aggressive defense of the INR at the current juncture could be futile.”

The strategic rationale: Why flexibility matters

Allowing the rupee to depreciate, rather than spending reserves to defend arbitrary levels, serves multiple strategic purposes:

1. Preserving Firepower

“An aggressive defense of the INR at the current juncture could be futile,” argues Sachchidanand Shukla. “Instead, two-way movement in INR can be used to absorb some of the global pressures, preserve FX buffers and allow market-driven adjustments that boost export competitiveness in a volatile world.”India’s forex reserves, while substantial at $696.6 (dec 26, 2025) billion, are finite. The Asian Financial Crisis showed that reserves can be depleted quickly when defending unsustainable levels. By allowing gradual depreciation, the RBI preserves reserves for genuine emergencies.

2. Export Competitiveness

A weaker rupee makes Indian exports cheaper in dollar terms, potentially offsetting some impact of US tariffs. With the REER having peaked at 108.14—indicating significant overvaluation—allowing depreciation helps restore competitiveness.Chief Economic Adviser Nageswaran emphasized this point, noting the falling rupee was “not affecting inflation or exports” negatively. In fact, a more competitive exchange rate could support export-oriented sectors like IT services, textiles, and pharmaceuticals.

3. Maintaining monetary autonomy

Most crucially, allowing currency flexibility preserves the RBI’s ability to set interest rates based on domestic needs. With inflation falling to historic lows (0.25% in October 2025), the RBI had justification to cut rates to support growth. Attempting to defend the rupee at a fixed level would have required keeping rates high despite low inflation—sacrificing domestic economic goals for an arbitrary currency target.

4. Two-way movement deters speculation

“Two-way movement in INR can be used to absorb some of the global pressures,” notes Sachchidanand Shukla. When the rupee only weakens (one-way movement), it becomes a profitable one-way bet for speculators. If they know the RBI will prevent strengthening but allow weakening, they can short the rupee risk-free.Two-way movement—allowing both appreciation and depreciation—makes speculation riskier and more expensive, naturally deterring some of it.

The road ahead: What this means for Rupee

Looking ahead, the rupee’s trajectory will depend on factors some of which are outside the RBI’s control:External Factors:

- US Federal Reserve policy and dollar strength

- US-India trade negotiations and tariff outcomes

- Global commodity prices, especially oil

- Geopolitical tensions and risk sentiment

Domestic Factors:

- India’s growth trajectory and FDI inflows

- Inflation dynamics and RBI’s rate path

- Fiscal discipline and current account management

- Structural reforms affecting competitiveness

What won’t change is the framework. India will continue prioritizing monetary independence and capital openness, accepting exchange rate flexibility as the price. The RBI will intervene to manage volatility, not defend specific levels.As Ranen Banerjee summarizes: “In the current policy choices made in the monetary policy, the rupee will find its own level with the Reserve Bank interventions being only for management of volatility as stated in its policy.”The impossible trilemma isn’t a theoretical abstraction. It’s a practical constraint that shapes decisions about interest rates, capital flows, and exchange rates. Understanding it is essential to understanding why the RBI responds to currency movements the way it does—and why allowing the rupee to find its level, rather than defending arbitrary bands, is not policy failure but policy by design.

Discover more from stock updates now

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.