New way to study surfaces brings ‘real world’ pressure to the lab

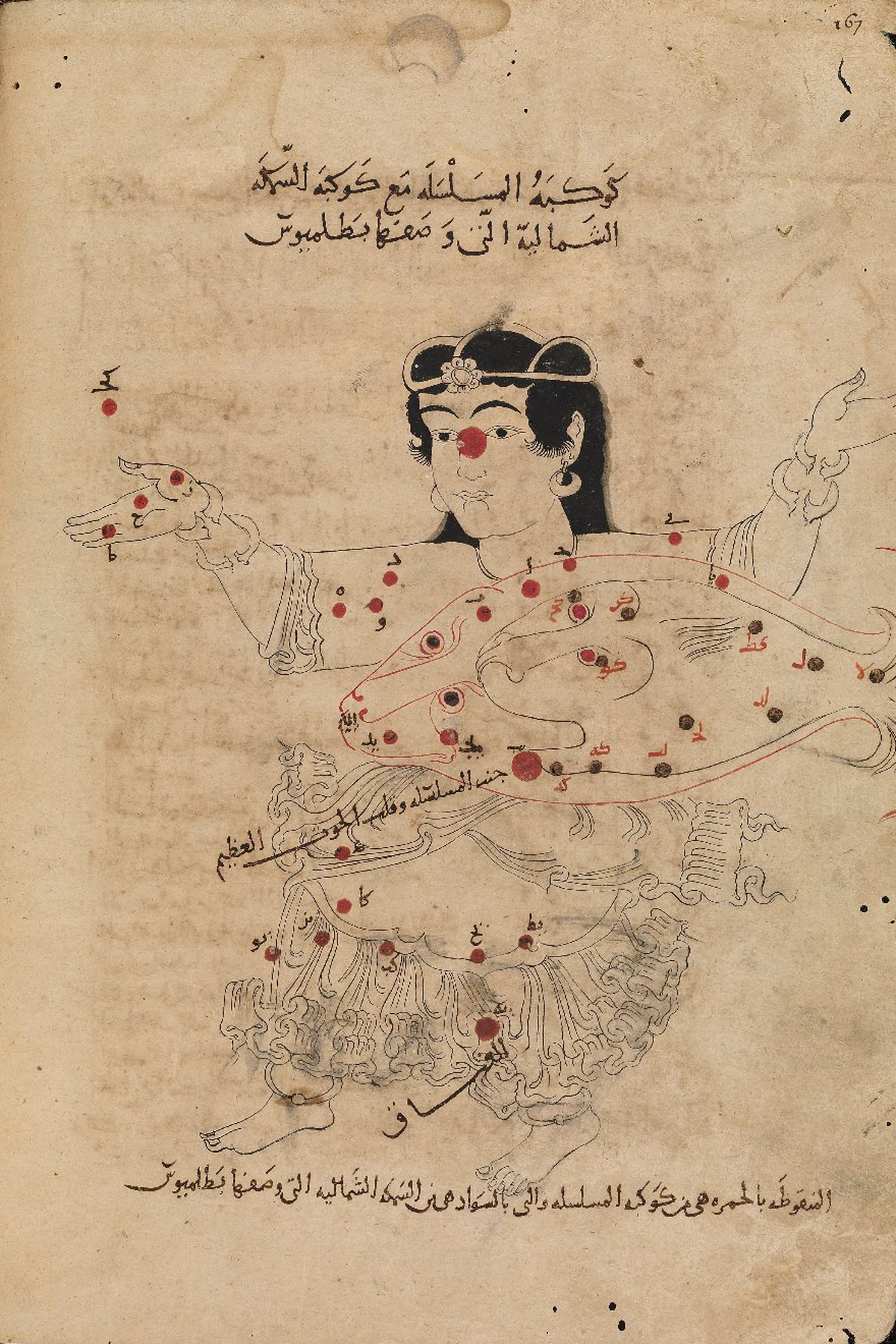

A schematic illustration of the experimental technique.

| Photo Credit: Cai et al., Photo Science, 2025

One of the best tools for this is X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS). A device shoots X-rays at a material and measures the properties of electrons that bounce off, revealing to researchers exactly what elements are present and how they’re bonding.

The problem is that there’s a major catch. XPS usually requires a vacuum (a space with no air). If there are gas molecules around, they block the electrons before they reach the detector. This creates a problem called the ‘pressure gap’.

While XPS works great in a vacuum, real-world chemical reactions usually happen under atmospheric pressure, about 1 atm. Studying a catalyst in a vacuum is a bit like trying to study how a fish swims by looking at it on dry land: you aren’t seeing its natural behaviour.

Currently, to bridge this gap, scientists often have to travel to large, stadium-sized facilities called synchrotrons.

Now, a team of researchers from ShanghaiTech University and other institutions has published a paper in Photon Science proposing a solution that could fit in a standard laboratory.

The researchers modified a standard laboratory XPS machine to handle high pressures. Their innovation was a piece of engineering usually associated with rocket engines: a de Laval nozzle.

A de Laval nozzle is a tube that pinches in the middle and flares out at the end. This shape accelerates gas flowing through it to supersonic speeds. In the study, the researchers used the nozzle to shoot a focused jet of gas directly at the sample surface.

According to the paper, the localised pressure creates a small zone up to 1 am right on the sample’s surface. Because the gas is moving so fast and is focused, the pressure drops off rapidly just a few millimeters away, keeping the rest of the machine in a vacuum, sparing the detectors.

The team used computer simulations and a custom pressure sensor to verify the pressure at the sample surface actually reached 1 atm.

To test the system, the researchers examined a sample of platinum while spraying it with nitrogen gas.

In a standard XPS machine, filling the chamber with this much gas would make it impossible to see the sample. But the researchers reported their gas jet created a layer of high pressure only about 20 µm thick, thin enough to also allow the electrons from the platinum to still reach the detector.

Per the study, the team successfully detected signals from both the nitrogen gas and the platinum surface at pressures up to 1 atm. They also found that as the pressure increased, the signal from the surface got fainter.

If the technology proves reliable, scientists could study surface chemistry at realistic pressures in their own labs, rather than applying for time at synchrotron facilities. They could also better understand how catalysts break down pollutants or how rust forms in real time, potentially leading to more efficient industrial processes.

Discover more from stock updates now

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.