Can India overtake Bangladesh in textile exports to the European Union?

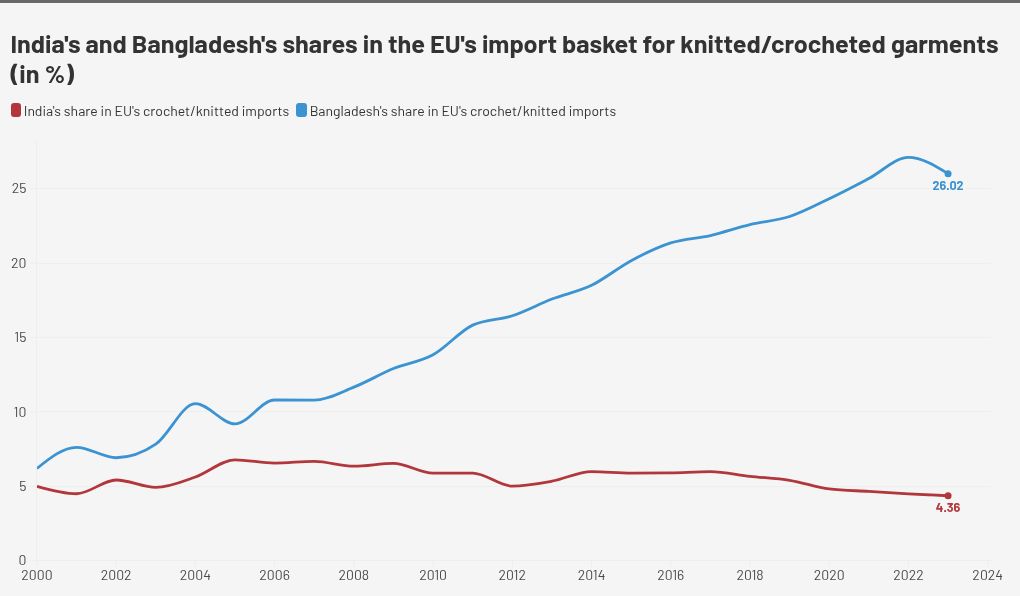

Within the textile value chain, India’s exports to the EU remain concentrated in intermediate products — particularly yarns and fabrics — rather than in finished garments such as T-shirts, shirts, and trousers. Bangladesh’s exports far exceed India’s in two readymade garment categories in particular — knitted or crocheted garments (such as T-shirts, jerseys, pullovers, sweaters, and cardigans) and woven garments (such as suits, jackets, trousers, dresses, and shirts).

As shown in the chart below, India’s share of the EU’s total imports declined from nearly 6.5% in 2009 to about 4.4% in 2023 for knitted/crocheted garments. Bangladesh’s share rose from just 6% in 2000 to 13% in 2009 and 26% by 2023.

A similar pattern is seen in the woven garments trade too. For woven garments, India’s nominal export value to the EU fell in absolute numbers from a peak of about $3.5 billion to $2.9 billion.

To understand why Indian garments have not been able to compete with Bangladesh in the EU market, we compared the average per-unit price of Bangladesh’s major export commodities. From the table below, it is clear that India’s unit values are consistently higher across all products.

This may indicate the following: First, India may be exporting more value-added, better-quality garments, which allows it to charge higher prices.

However, its low market share reveals that the EU’s demand for such products is limited relative to mass-market apparel, suggesting that ‘premium positioning’ (if at all) alone cannot drive volume. Second, and more likely, is that higher prices may reflect structural disadvantages: higher production costs, less integrated supply chains and logistical inefficiencies.

Furthermore, the tariffs faced by Indian and Bangladeshi products are radically different. Bangladesh, as a LDC, has enjoyed duty-free, quota-free access to the EU under the Everything But Arms (EBA) scheme.

Crucially, this zero-tariff access applies even when garments do not meet the EU’s standard ‘double transformation’ requirement.

This means Bangladesh can import fabric from anywhere in the world, stitch garments domestically, and export them to the EU at zero duty. India, lacking such preferential treatment, has faced EU Most Favoured Nation (MFN) tariffs of around 12%.

Internal factors also matter. Over the past three decades, Bangladesh has unilaterally and consistently promoted the garment sector. India’s approach, by contrast, has been fragmented. Yet, the balance may be poised to shift. Two major structural breaks are on the horizon.

First, Bangladesh is set to lose its EBA benefits in 2029. This would mean the end of automatic duty-free access to the EU, with apparel exports potentially facing MFN tariffs of around 12%. Bangladesh is then expected to seek entry into the EU’s Generalised Scheme of Preferences Plus (GSP+), which offers zero tariffs on roughly two-thirds of tariff lines, including textiles. However, GSP+ comes with stricter rules of origin (RoO) and safeguard provisions.

As Bangladesh is heavily reliant on other countries (including India) for fabrics, this could mean that Bangladesh’s garments may not satisfy GSP+ RoO for duty free entry. Bangladesh, will of course, try its best to negotiate its way out of this clause.

Historically, EU has maintained its stance on the double transformation criteria. In case it continues to do so, Bangladesh will be at a serious disadvantage. If competition is price-driven, then Bangladesh may lose its market share. If, on the other hand, Bangladesh’s primary advantage comes from supply-chain integration, then it could still retain dominance in the face of higher tariffs.

The recently finalised agreement grants India duty-free access to the EU’s textile markets, subject to the double-stage processing requirement. Since India’s textile industry is already relatively vertically integrated — most of the yarn and fabric used in apparel production is manufactured domestically — the double-stage requirement is not likely to be an impediment for Indian textile exports. As a result, Indian exporters are well-positioned to meet stricter rules of origin without major restructuring.

Taken together, these changes create a rare window of opportunity: narrowing of Bangladesh’s preferential advantage and reduction of India’s tariff disadvantage. Textiles remain one of the largest employers in Indian manufacturing, spanning both formal and informal enterprises, yet the sector has failed to create employment opportunities in recent years.

Reviving textile exports, particularly to high-income markets like the EU, could act as a much-needed tonic for India’s employment crisis. The question is whether India is finally ready to tailor a strategy that fits, capturing market share with cost-competitive production, vertical integration, and a coherent industrial policy.

The recent experience of Vietnam’s apparel exports, which saw a surge post the signing of the EU-Vietnam FTA in 2020, is indicative of the opportunities on the horizon for India.

Anwesha Basu and Arnab Chakrabarti are Assistant Professors in the Department of Economics, FLAME University

Published – February 18, 2026 07:00 am IST

Discover more from stock updates now

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.