Private sector seeks anchor contracts as Dept of Space struggles to use funds

The Economic Survey 2025-26, however, which was tabled in Parliament today, has read the events of the last decade not as a period of struggle but one of export consolidation. It noted that between 2015 and 2024, India launched 393 foreign satellites for 34 countries, earning over $143 million and €272 million.

But it’s possible that this revenue stream is masking the Department’s internal structural fragility. The space industry has been clamouring for a historic budget hike to fund a projected $44 billion space economy over the next decade, a figure that the Survey backs, including upstream launch and satellite manufacturing and downstream applications and services. So the Department needs to balance the promises of human spaceflight and a space station against the unglamorous need to fix the manufacturing issues threatening its primary launch capability.

Capacity to absorb

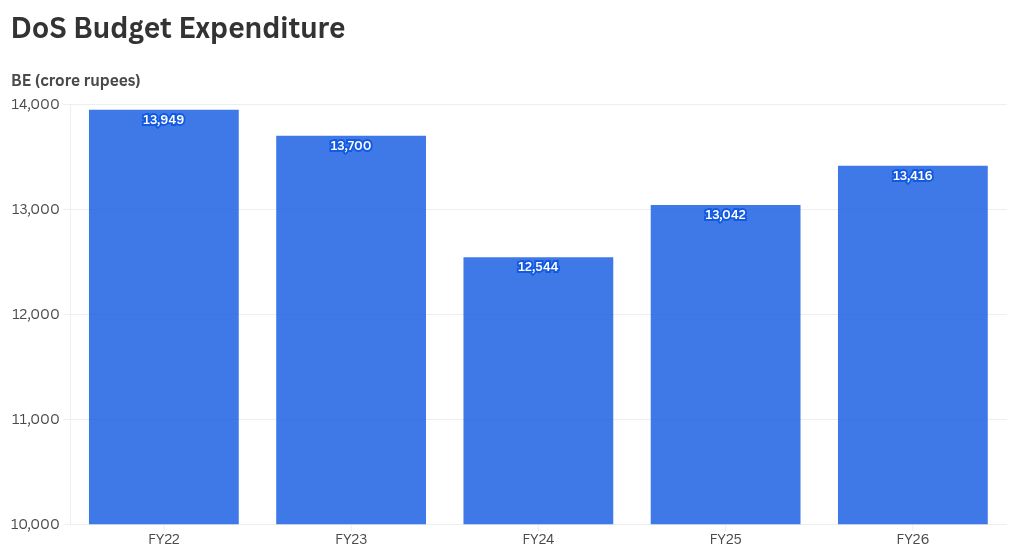

The Budget Estimates (BE) have grown minimally over the last four years. Between FY22 and FY26, the nominal allocation decreased and then recovered slightly, effectively shrinking when adjusted for inflation.

The Department of Space has consistently failed to use up its initial allocations, leading to progressive downward revisions in the Revised Estimates (RE), weakening the case for a larger increase in the FY27 budget. (The Finance Ministry has historically preferred a greater capacity to absorb funds over fulfilling ambitions.)

In FY22, the capital expenses, on assets like new launch pads, spacecraft, etc., was ₹8,228 crore but by FY26 it had dropped to ₹6,103 crore. Conversely, revenue expenditure such as salaries and for operations rose from ₹5,720 crore in FY22 to ₹7,311 crore in FY26. Thus the budget is increasingly consumed by operational costs rather than new infrastructure or R&D assets. This is a worrying trend for a technology-intensive organisation whose competitiveness in the long term depends on sustained capital formation.

The government appears to be betting that NewSpace India, Ltd. (NSIL) — ISRO’s commercial arm — can plug this capital gap. The Survey pointed out that the NSIL’s revenue surged from ₹322 crore in FY20 to ₹2,940 crore in FY23, with the implicit strategy being to replace tax-funded infrastructure with growth funded by commerce, even as the core R&D budget stagnates.

‘Critical infrastructure’

Both the Satcom Industry Association-India (SIA-India) and the Indian Space Association (ISpA) have formally articulated their funding and policy demands for the FY27 budget. SIA-India in particular has been vocal about the financial scale required. In its pre-budget submission to the Finance Ministry, the body said the current allocation of about 0.04% of GDP is insufficient and that it needs to reach 0.12%. It recommended a roadmap in which the FY27 target is ₹18,000 crore, to be earmarked for a ‘National Satellite Connectivity Mission’, expanded launch infrastructure, and a hybrid production-linked incentive (PLI) scheme tailored to low-volume, high-reliability space components.

To understand how ambitious the ₹18,000 crore request is, one need only look at the Survey’s data on private capital: India’s entire ‘NewSpace’ ecosystem raised just over ₹1,000 crore in FY23. In other words the industry effectively wants the government to inject 18x the amount of private capital raised in a single year, turning the state into the primary venture capitalist.

ISpA, which represents major private players including Bharti Airtel, L&T, etc., asked that the space sector be classified as “critical infrastructure” in the FY27 budget. This is a financial mechanism to lower the cost of borrowing for private space firms. And instead of just asking for government grants, it demanded a policy where the government required 50% of all space-based services and hardware be procured from the domestic private sector.

The rationale was that predictable demand, with the government as an anchor customer, is more valuable than R&D subsidies, i.e. shifting from ‘Department spending on itself’ to ‘Department buying from industry’. This model is closer to NASA’s services-driven procurement approach than to ISRO’s traditional asset ownership.

Building confidence

Leading private firms have echoed these sentiments and have often focused on specific fiscal operational hurdles rather than just the total budget size. For instance the founders of Dhruva Space and SpaceFields have argued for shifting from owning assets to ‘data-as-a-service’ contracts and want the FY27 budget to allocate funds to buydata from private constellations rather than building government satellites to do the same job.

Some venture capitalists have also articulated a need for mission-linked procurements with multi-year visibility and for the budget to fund long-term pilot programmes, e.g. for disaster monitoring, that give investors the confidence to back space startups. This could help in a regulatory environment in which export controls and licensing delays continue to suppress commercial demand.

Taken together the gap between what the industry wants and what the Department of Space needs has never been wider. The industry wants ₹18,000 crore, critical infrastructure status, and a minimum procurement mandate — while the Department struggles to spend ₹13,000 crore, faces more scrutiny over its launchers’ reliability, and needs to audit its own supply chain. This divergence is made worse by the fact that different Department of Space programmes such as human spaceflight, launch vehicles, earth observation, and strategic missions also enjoy unequal political backing.

Transition plan

One way out is operational consolidation. Following the recent launch anomalies, the Department can redirect funds towards rigorous quality assurance and rectifying supply chain defects to restore confidence in ISRO’s launchers. In fact the Economic Survey has inadvertently offered the best argument for this approach, noting that global manufacturing acts as an “institutional stress test, exposing weaknesses that sheltered activities can conceal”. The recent launch failures are exactly that: the result of a sheltered state monopoly suddenly facing the stress test of commercial demand requiring a high launch cadence.

Second, with capital allocation dropping, the Department of Space needs to prove that it can actually spend money on infrastructure, e.g. the second spaceport at Kulasekarapattinam, rather than surrendering funds at the RE stage. As the human spaceflight mission targets a 2026-2027 timeframe, the budget must also transition from developmental funding to operational safety.

Finally, the Department of Space needs a plan that says which missions and services will shift from being assets built by the government to those provided by industry, and on what timeline. Without strengthening IN-SPACe’s capacity to award and manage complex multi-year service contracts, the industry’s demand for the government to be an anchor customer could overshoot the state’s ability to create a reliable market that private firms can confidently invest in.

mukunth.v@thehindu.co.in

Published – January 29, 2026 03:05 pm IST

Discover more from stock updates now

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.