Why only female Darwin’s bark spiders weave the toughest webs

The Darwin’s bark spider (Caerostris darwini), found in the forests of Madagascar, weaves silk that outperforms steel and most human-made fibres in both strength and toughness.

Larger webs, stronger threads

Its silk has a tensile strength of about 1.6 gigapascals, around 3x higher than that of iron, making it the toughest biological material ever tested. But as scientists are now finding, this extraordinary strength isn’t something every individual produces.

Across spider species, body size is often linked to silk quality. Larger spiders generally produce tougher silks to capture larger or faster prey. In orb-weaving spiders such as the Darwin’s bark spider, larger bodies over evolutionary time have accompanied larger webs and stronger silk threads.

Scientists from institutions in China, Madagascar, Slovenia, and the US studied bark spiders to understand the conditions in which they produce the tough silk. Their findings were recently published in Integrative Zoology.

Three hypotheses

The study focused on two bark spider species in Madagascar: Caerostris darwini, which spins the largest orb webs ever recorded, and its close relative Caerostris kuntneri.

Egg sacs from both species were collected from Analamazaotra National Park and the spiders were raised in laboratory conditions. This allowed the scientists to compare silk produced by males and females at different life stages while keeping environmental factors such as diet and humidity constant.

The team tested three competing hypotheses. The first proposed that all individuals — males and females, juveniles and adults — produce silk of similar toughness. The second suggested only females produce tougher silk, regardless of size. The third said only large individuals, especially large adult females, produce exceptionally tough silk as and when their body size and ecological role demand it.

Dragline silk

The size difference between male and female bark spiders is striking. In C. darwini, adult females are about 3x larger than males. In Caerostris kuntneri, they can be up to 5x larger, suggesting that females are under much stronger evolutionary pressure to invest in tougher silk.

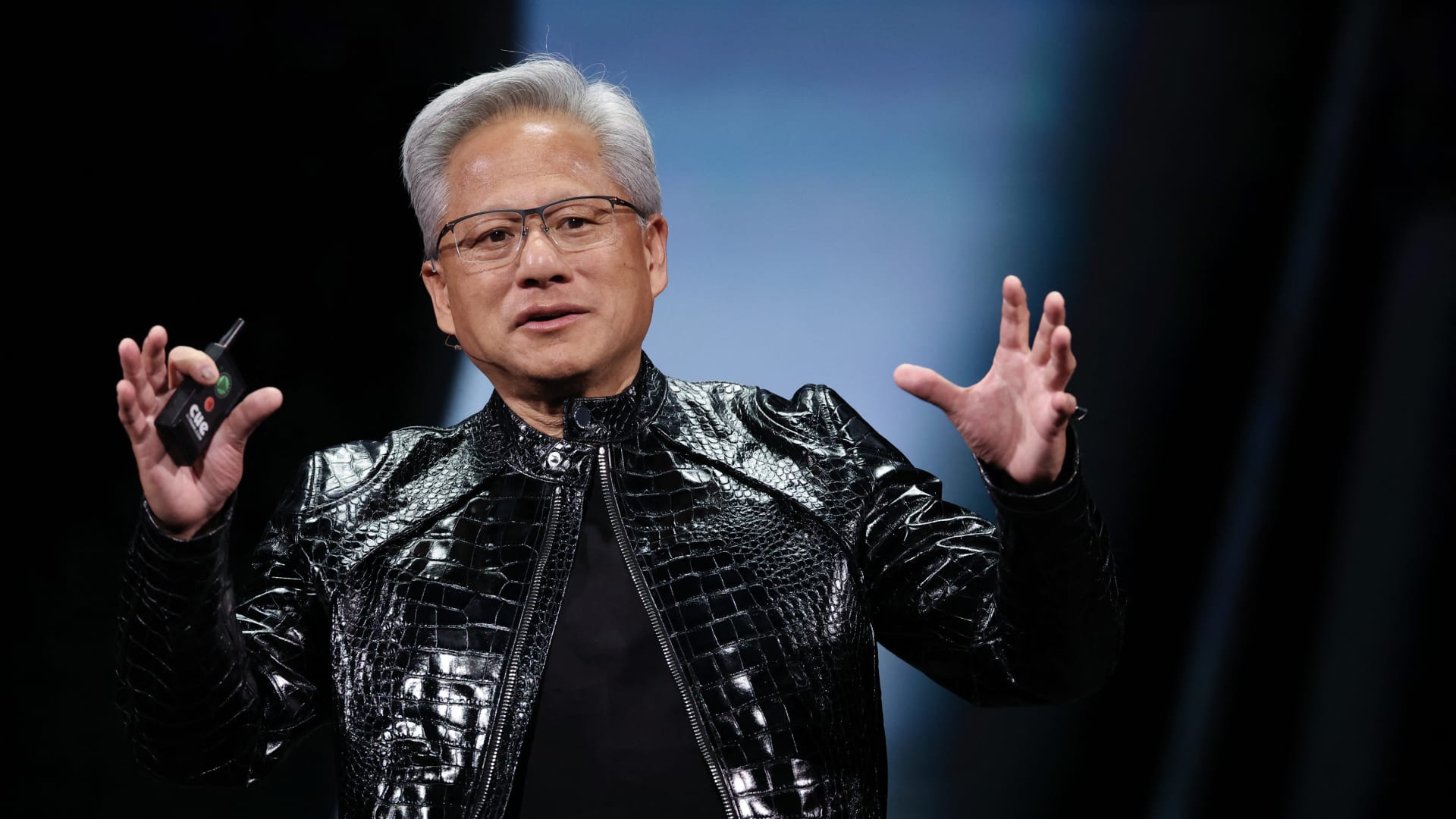

A Darwin’s bark spider in Madagascar, 2010.

| Photo Credit:

Matjazgregoric (CC BY-SA)

To measure silk quality, the researchers collected dragline silk, also known as major ampullate silk, from spiders of both sexes and at different life stages in each species. Each strand was carefully mounted on a cardboard frame and stretched to test its strength, stiffness, and ability to absorb energy before breaking.

Dragline silk is one of the most important types of spider silk. Nearly invisible to the naked eye, it forms the structural backbone of an orb web and serves as safety lines, anchor threads, and emergency escape ropes for the spiders.

Producing this silk, however, is metabolically expensive. The energy required to synthesise the amino acids that make up dragline silk varies; some such as proline, which plays an important role in making silk elastic, are particularly expensive.

Darwin’s bark spider silk contains unusually high levels of this protein, explaining its exceptional mechanical properties but in turn increasing its metabolic cost.

Quality and architecture

The study’s results were unequivocal: only large adult females produced exceptionally tough silk. Their silk was also stiffer and more capable of absorbing far more mechanical strain before breaking than the silk produced by males or juveniles. The silk from adult males and juvenile males and females was mechanically indistinguishable.

The study also found that adult females produce high-performance silk only when it’s biologically necessary. As the females grow larger and begin building large webs capable of intercepting fast-moving prey, they ‘turn on’ on the physiological machinery required to manufacture the superior silk.

The study also uncovered a close link between silk quality and the architecture of the web. Adult female Darwin’s bark spiders build more sparse webs, with wider gaps between threads, using less silk per unit area. Despite being economical, these webs are highly effective because each thread can absorb (relatively enormous forces. Juveniles and males on the other hand spin more dense webs made of metabolically cheaper and weaker silk.

Curiously, not all the properties of the silk varied with size and sex. Regardless of age or sex, all individuals produced silk of comparably high stretchability, or how much the silk could be stretched before it broke. It suggested that the elasticity of the silk of spiders of the genus Carostris is a genetically conserved feature — while extreme toughness is tuned according to body size and ecological demand.

Time versus energy

At the molecular level, differences in silk properties arise from changes in protein composition, how the proteins are arranged and cross-linked, and even the shape and length of the ducts that spin silk inside the spider’s body. C. darwini has an unusually long and complex spinning duct that scientists believe could be allowing silk proteins to produce exceptionally strong silk fibre.

The trade-off however is time and energy. Female bark spiders produce less silk overall, take longer to rebuild their webs, and invest more in quality over quantity.

“We think that very tough silk evolved because it was needed to structurally support the huge webs built by Caerostris spiders, rather than as an adaptation to hunt any specific prey,” Matjaž Gregorič, the lead author of the study and a researcher at the Jovan Hadži Institute of Biology, Slovenia, said.

The strategy pays off in the spider’s distinctive habitat. C. darwini builds enormous webs, up to 25 m wide, suspended over rivers and lakes. These aerial traps allow the spider. to capture swarms of flies and beetles that few other spiders can.

Silk production in Darwin’s bark spiders has evolved to ensure energy is invested only where it can yield a greater survival advantage. The extraordinary properties of its silk thus emerge from a complex interplay between body size, sex, ecology, and behaviour.

Ipsita Herlekar is an independent science writer.

Published – January 21, 2026 05:30 am IST

Discover more from stock updates now

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.