Microbe might spark first stages of ulcerative colitis: new study

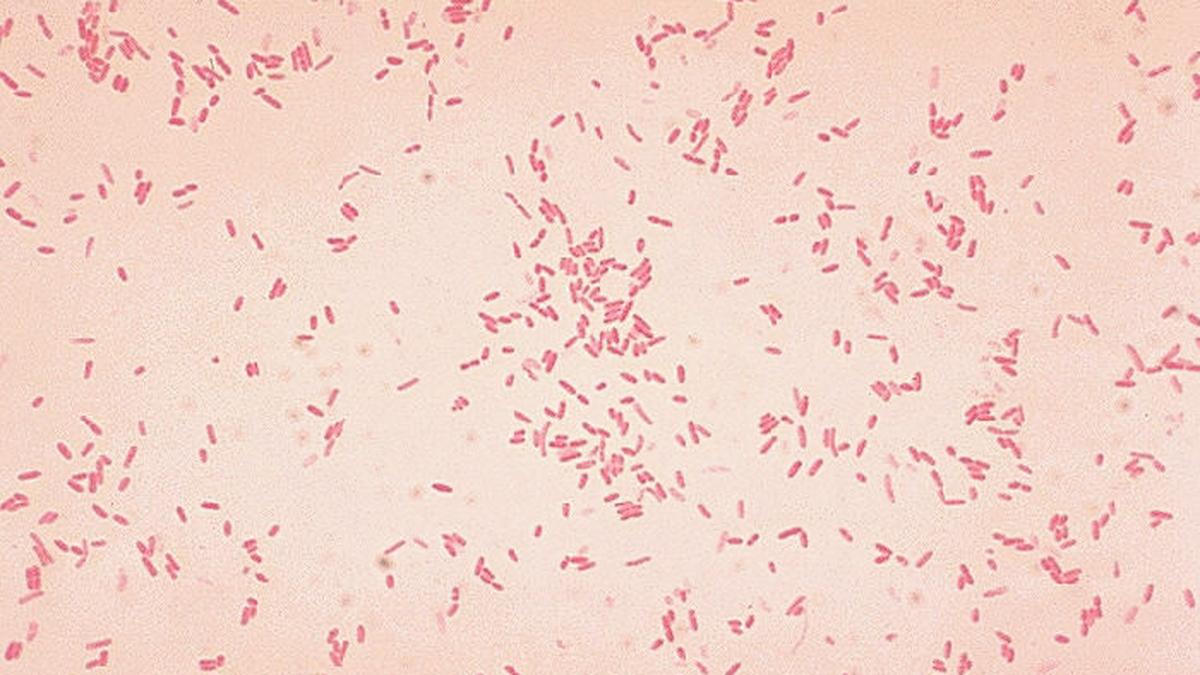

But a new study has argued that the disease may actually start earlier, when a normally hidden layer of immune cells just beneath the gut lining begins to become thinner. Specifically, the study — published in Science and led by scientists at Nanjing University, China — identified a strain of Aeromonas bacteria that selectively damaged the macrophages that reside in this layer.

Nanjing University Medical School gastroenterology professor and study co-author Minsheng Zhu said the aerolysin produced by the Aeromonas bacteria could be an initiating factor in ulcerative colitis by disrupting the macrophage barrier.

AIIMS Delhi gastroenterologist Vineet Ahuja called the work “a landmark study” that indicated how well microbial triggers could shape inflammatory bowel disease (of which ulcerative colitis is one form).

“The microbiome may or may not be the primary cause but it is nevertheless a very significant trigger,” he said.

First strike

The researchers obtained surgical colon samples from 17 patients with ulcerative colitis. There, they found that the density of macrophages in regions that appeared intact under the microscope had actually dropped by about 67% compared to healthy controls.

Because these cells sat just beneath the gut lining, their loss wasn’t visible on routine scans or endoscopy, making the early damage easy to miss. These sentinel cells ordinarily clear bacteria that penetrate the epithelial surface and help maintain immune balance. Their depletion, the study’s authors suggested, represents an early breach that could set the stage for later inflammatory cascades.

The team traced this vulnerability to a subset of Aeromonas bacteria that could produce aerolysin, a pore-forming toxin that proved dramatically more potent against macrophages than against epithelial cells. The toxin also left the gut’s surface cells largely intact at first, targeting macrophages long before any epithelial damage could be detected. Laboratory tests showed that a substantial proportion of faecal samples from the patients released macrophage toxic factors and follow-up checks pointed to aerolysin as a major driver.

In a larger screening study, researchers found Aeromonas in 72% of ulcerative colitis patients but in only 12% of healthy controls and that a subset of patients may carry harmful versions of the bacterium. For them, therapies targeting Aeromonas or its aerolysin could represent a personalised treatment approach, Prof. Zhu said.

Noting that the authors “designed an elegant series of experiments” to test their hypothesis, Gilaad Kaplan, gastroenterologist and epidemiologist at the University of Calgary in Canada, also emphasised the human data was cross-sectional. This means researchers can’t yet say whether aerolysin-producing Aeromonas appears before the disease or proliferates because of it. Factors such as smoking, diet, and antibiotic exposure could also influence microbial patterns.

How the shield falls

To understand the aerolysin’s effects, the team used mouse models. Exposure to aerolysin rapidly depleted intestinal macrophages and rendered the animals highly susceptible to chemically induced colitis, which led to inflammation, diarrhoea, and weight loss. Mice colonised with an aerolysin-deficient version of the bacterium didn’t develop severe disease, however, nor did germ-free mice. This suggested both the toxin and a permissive microbial environment mattered.

The findings fit a broader pattern researchers have observed in microbiome research. Rutgers University professor of applied microbiology Liping Zhao said a healthy gut ecosystem naturally resists colonisation by harmful invaders because of a stable ecological structure he called the “two competing guilds”. In healthy individuals, the “foundation guild” of microbes that ferment fibres and produce short-chain fatty acids maintains acidity, sustains the mucus barrier, and consumes oxygen — all conditions that exclude organisms that produce toxins.

“When this system is disturbed through infection, antibiotics or long-term low-fibre diets, the foundation guild weakens and the pathobiont guild expands,” he said.

His team’s analysis of 38 datasets across 15 diseases published last year in Cell concluded that this shift creates metabolic and immune conditions that favour opportunistic bacteria associated with inflammation. In these conditions, even rare environmental invaders such as the particular Aeromonas strain can colonise.

Prof. Zhu said this pattern of destabilisation was also mirrored in their own mouse experiments.

New treatment paths

Prof. Ahuja said the work also strengthens the case for microbiome-based therapies for ulcerative colitis, including targeted strategies like antibodies that neutralise toxins. This is an important prospect because current drugs that modify the immune system are expensive, have significant side effects, and benefit only 50-60% of patients.

The findings of the new study also open potential diagnostic avenues. If future tests can confirm that distinct groups of ulcerative colitis patients harbour the toxin-producing Aeromonas strain, clinicians could one day classify patients by microbial subtype. In mice, antibodies that neutralised aerolysin prevented the onset of colitis and even partially improved established disease, pointing to interventions focusing on the toxin as a possible strategy.

Finally, experts said, the study points to a new way of thinking about how the disease begins: one where vulnerability takes shape long before symptoms appear, reinforcing the idea that ‘treating’ the microbiome may one day be as important as suppressing inflammation.

Much also remains uncertain, however. Although Prof. Kaplan said the results were provocative and added “an interesting dimension to ongoing research into microbial drivers of inflammation”, there is currently no epidemiological evidence linking Aeromonas exposure to ulcerative colitis. Researchers will need long-term studies to clarify whether the bacterium helps set the disease in motion or is “simply a passenger along for the ride”, in his words.

Per Prof. Ahuja, India is also conducting large clinical trials of faecal transplants and diet modification for inflammatory bowel disease, funded by the Indian Council of Medical Research. This infrastructure could establish early platforms on which future mechanistic insights, such as those raised by the new study, can be explored.

Anirban Mukhopadhyay is a geneticist by training and science communicator from New Delhi.

Published – December 31, 2025 05:30 am IST

Discover more from stock updates now

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.